And we’re back! Spoilers for Dororo this week, previously discussed in this post.

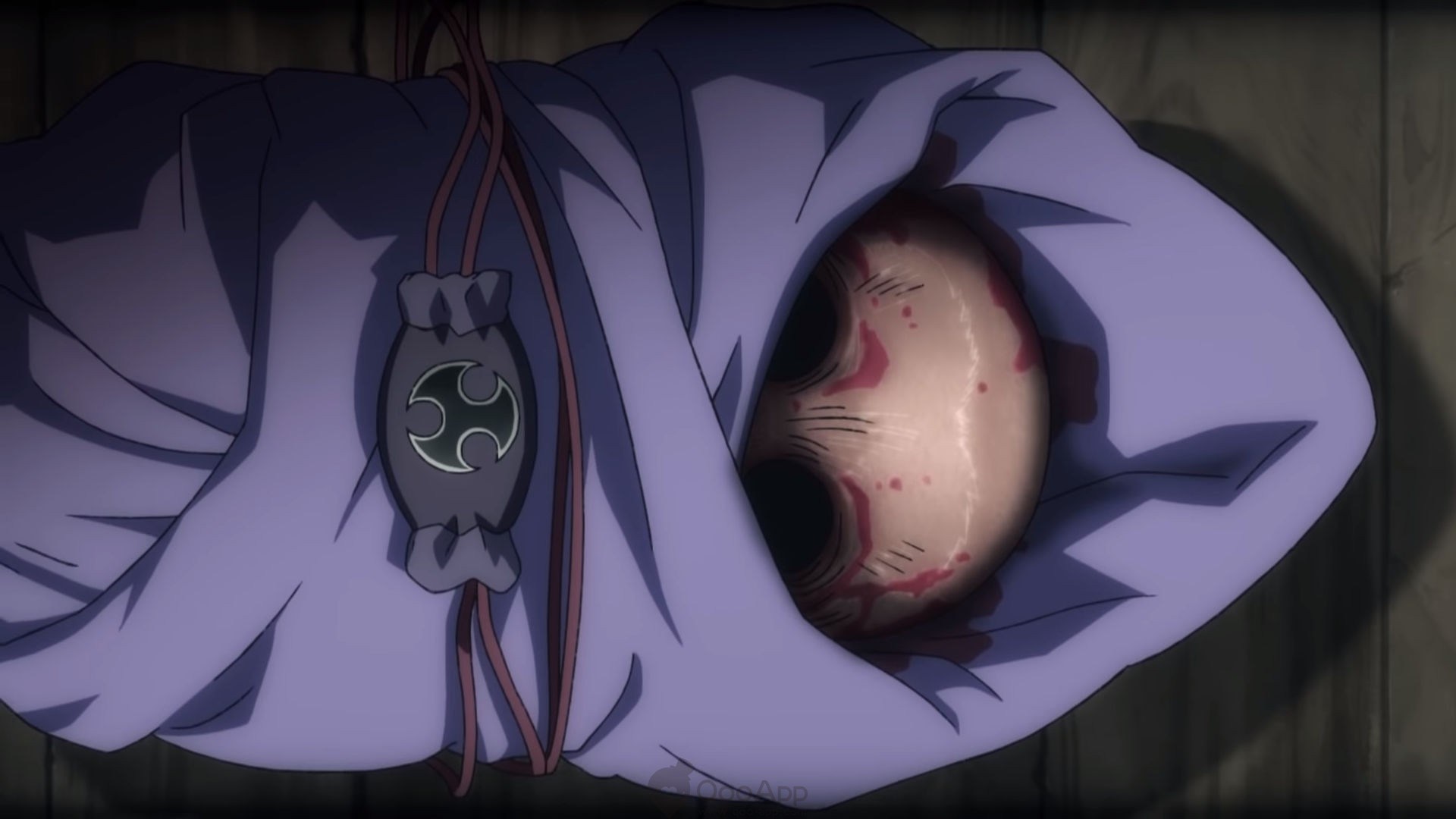

The baby should never have lived.

Hyakkimaru, the rightful heir to the Daigo name, was meant to die. His death, in the mind of his father, was necessary, noble. It was right. Hyakkimaru belonged to him. If Kagemitsu chose to give his son over to demons to further his own ambitions and to protect his property – the people and lands he ruled over – then, well, that was just the way things were.

But things did not go as planned. Hyakkimaru lived. And, once he was able, he began fighting across the country, searching for what was his.

This is the main plot of Dororo, and it’s a horror story wrapped up in action and adventure. Like all the best horror stories, it has depth. It forces you to question. And what Dororo wants you to question is the nature of sacrifice.

Sacrifice is noble when it is chosen, and evil when it is not.

Sacrifice, in Dororo‘s case, is largely a question of bodily autonomy, and the question is twofold: first, who has the right to your body? Second, does one person’s bodily autonomy outweigh the needs of society?

During this anime, different characters answer this question in different ways. Kagemitsu is certain that he has the right to his son’s body. The demons ask for something that belongs to him, and he gives them his son in response. This perspective is one of filial piety and a profoundly patriarchal feudal tradition. Just as the body of Hyakkimaru is seen to belong to Kagemitsu by virtue of parentage, so are the bodies of the people who farm the fields of his lands by virtue of location. Therefore, Kagemitsu’s choice is a weighing of two things he owns. He gives one up to make the other better, therefore increasing its value in a way that benefits him directly.

But his choice ignores that Hyakkimaru has feelings of his own.

This becomes readily apparent in the scenes where Hyakkimaru confronts his family. His younger brother, horrified at what has been done to Hyakkimaru, nonetheless chooses to support his father’s actions for the apparent good of the lands held by their family. His mother, who had previously attempted to protect him, throws off that protection, it seems, because Hyakkimaru has chosen to take back what belongs to him: the pieces of his body that his father traded away. Dororo, the innocent bystander in this tumultuous exchange, is horrified. His (Dororo is a girl but chooses to live life as a boy for the duration of the anime) own parents chose to sacrifice themselves for him and for his future. To Dororo, that sacrifice of the self was painful but also honorable. To sacrifice their own son? That is evil and wrong.

Yet even Dororo begins to question Hyakkimaru’s actions when it becomes apparent just what choosing to take back his body costs others.

It’s no accident that the questions raised in this anime are ones that I find really intriguing. They’re questions that our society is currently wrestling with within the contexts of prison labor, privacy, the abortion debate, and more. It is unquestionable that you have the right to your own body – until suddenly that right impacts the wealth, health, or convenience of others.

Dororo is the character that clearly articulates this within the anime. He asks Hyakkimaru, “Did we do the right thing?” following a particularly dark episode “The Story of the Scene from Hell”. In this episode, killing the demon that had Hyakkimaru’s spine destroyed the village it was protecting. It resulted in the death, either directly or eventually, of the residents of that village, which heretofore had looked idyllic and peaceful. Yet the villagers took and used the bodies of more than just Hyakkimaru to feed that peace. Hyakkimaru is only the child that survived.

It is easy to dislike the villagers because they aren’t exactly nice people. They try to kill Dororo, and do murder a bunch of other children, as well as the nun who sheltered them. Our sympathy lies with Hyakkimaru as he attempts to regain sovereignty over his own body. Yet Hyakkimaru does not seem to feel compassion for the innocents whose lives he may worsen with his quest. We accept that unease, as viewers. After all, those who gave him away were self-motivated. They aren’t moral either. Trading his health and well-being for a collective benefit to immoral people is not acceptable. Revenge has a cost. Yet Dororo cannot accept that unease, and questions such easy acceptance of the violence that happens to others in the wake of Hyakkimaru’s rage.

The moral conflict in this episode reminded me of Ursula LeGuin’s wonderful tale “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.” In this tale, it is only one child who is tortured for the good of a whole city. A utilitarian interpretation of this allows for a certain forgiveness of this status quo. After all, the people in Omelas are all fundamentally good – except for this one sin. Yet some people choose to walk away into suffering rather than participate in a system that is inherently immoral. They cannot tear down the system – they cannot subjugate their neighbors to their own choice. They can only walk away. They can’t free the child.

Hyakkimaru chooses to emancipate himself as the child in Omelas cannot. And he is not the only child sacrificed. Yes, the people in the moth village live an idyllic life, but they regularly feed travelers and children to moth demons. Even if it were possible for one child to pay such a sacrifice for peace and for that peace to be an ethical one (rightly debatable within LeGuin’s tale) that is not what is happening here. That sacrifice of one child is not enough – can never be enough. The demons are too hungry.

In the end, enforcing your own moral choices on others is its own kind of evil. If you want to give up your body, give it up. But you cannot demand it of someone else just because they are conveniently there to take on the sacrifice for you. This, I think, is the lesson of both Hyakkimaru’s journey and Omelas. Sacrifice is a choice. Who chooses that sacrifice is just as important as who makes it. And the choice to destroy someone else for your own gain, once made, is easily made again, and again, and again.

Want to support this blog? Buy books, make a Paypal donation, or subscribe to my Patreon.

Leave a comment